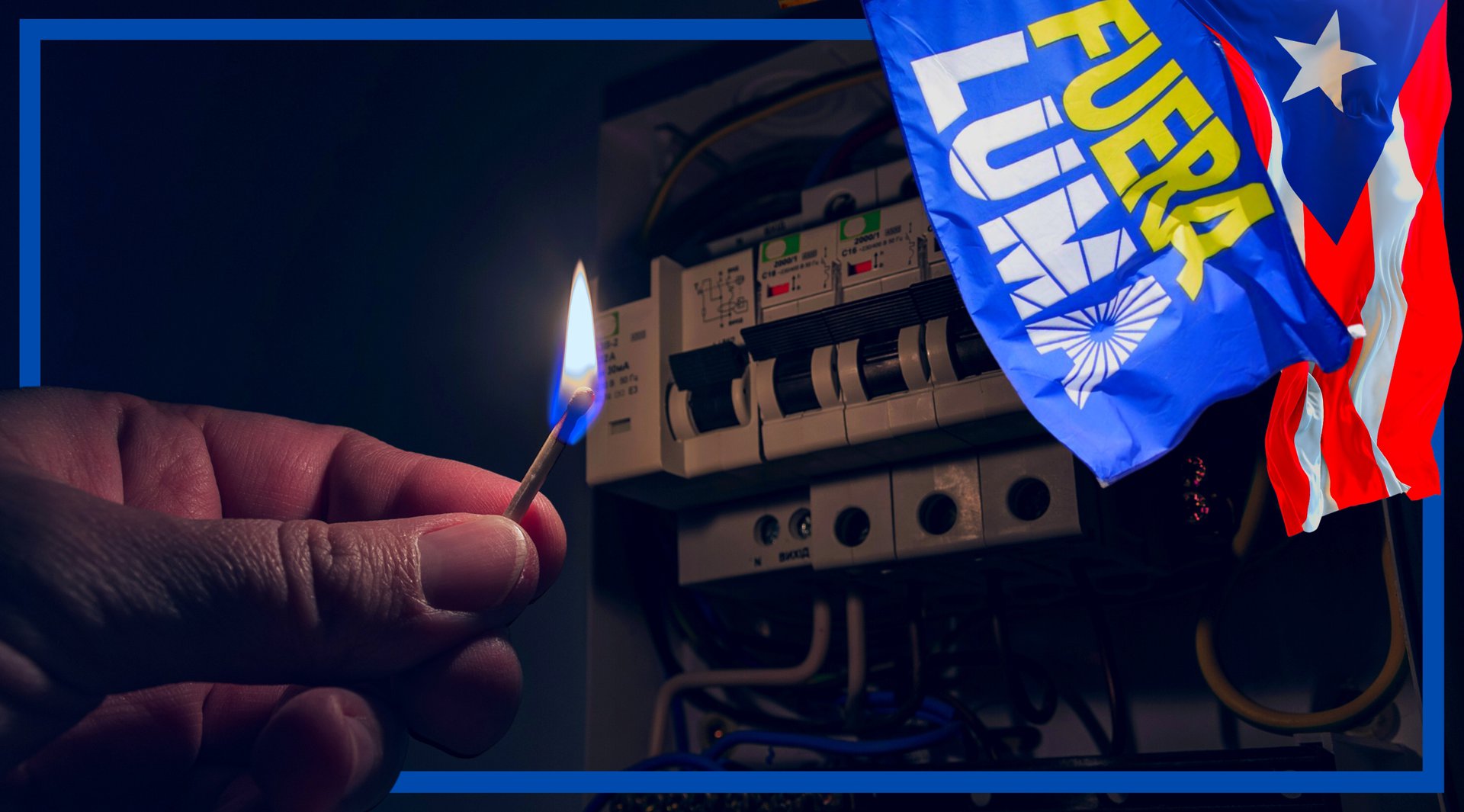

In Puerto Rico, medical clinics store life-saving medicine in freezers running on backup generators. Local residents struggle to keep perishable foods and clean water. They line up at gas stations with plastic fuel cans. And this has become the normal state of affairs due to the failing power grid and the debt crisis.

Meanwhile, the state is insolvent while the U.S. continues to extract its pound of flesh through an unelected oversight board. As usual, everything is tied up in U.S. courts, which always favor the rights of businesses over those of citizens.

This is Part 3 of a three-part series. Part 1 explored Puerto Rico’s own investigations into how the bond fraud set the country back in terms of its electric grid. Part 2 examined how Wall Street helped bankrupt the country and the puzzling lack of action from regulators and law enforcement.

Part 3 is a deeper look into allegations of corruption and conflicts of interest among those who seemed to benefit from the disaster. We’ll also explore which politicians and contractors have been able to land contracts for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction.

Backstory: Disaster Capitalism in Puerto Rico

U.S. contractors have treated Puerto Rico’s financial and environmental disaster as a cash cow, perfecting what Noami Klein called “disaster capitalism.” However, on November 30, the island’s internal political forces and external financial forces faced a reckoning on the day when the largest contractor, LUMA Energy, was due to renew for another 15 years.

Puerto Rico and its public utilities should have been allowed to declare bankruptcy, but the creditors and bondholders wouldn’t allow it, so Congress and U.S. courts acted to protect high-net-worth investors at the expense of the people of Puerto Rico.

The Supreme Court had the opportunity to stop the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) but voted to uphold it. The FOMB appointed by Congress claims to have sovereign immunity, meaning it cannot be sued by residents of Puerto Rico.

With the PROMESA legislation, Congress gave power to a Financial Oversight Management Board (FOMB), chalked full of unelected political cronies, who corrupted the entire process by hiring McKinsey & Co., a highly conflicted consulting firm.

For Puerto Ricans, it’s the same old, same old, and they are up in arms. At recent demonstrations against LUMA, protesters clashed with police officers, and a photojournalist was attacked. And on November 22, the New York Police Department received a tip about a supposed terrorist threat against the company and its staff, which has now been shared with the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security Investigations.

As the tragedy of Puerto Rico’s losses of life from hurricanes is made into a farce by venal U.S. politicians and businessmen, Puerto Rico learns what Mexicans acknowledge with grim sarcasm: “Estamos tan lejos del cielo y tan cerca a Estados Unidos” or “We are so far from heaven and so close to the U.S.”

Who Benefits? Who Pays?

The litigation over Puerto Rico’s debts and its reconstruction is ongoing, and after six years of wrangling, PREPA bondholders and the FOMB are deadlocked. On one side are the politicians and organizations of Puerto Rico, who rightly feel that the U.S. has dealt them a raw deal. On the other side are the bondholders who point out that in normal bankruptcy proceedings, public employees getting bonuses is absolutely unheard of.

What is notable about Puerto Rico OBoard stiffing bondholders to pay cash bonuses to public employees is that no one ever hears of mainland govt employees receiving a cash bonus (and their govts are solvent & pay their debts). #muniland

— Cate Long (@cate_long) November 28, 2022

In the middle of contention is LUMA Energy, a consortium of Quanta Services and ATCO. LUMA was created expressly for Puerto Rico’s reconstruction, and everything the company does is put under a microscope.

After undercutting other bidders by $30 million, LUMA Energy was given charge of transmission and distribution of power on the island, while the Puerto Rican Electric Power Authority or PREPA is responsible for power generation.

Many Puerto Ricans blame LUMA for rising energy costs, and LUMA’s name appears on the electricity bills of residents, but it does not decide the rate its customers pay for electricity. LUMA reports to Puerto Rico’s Energy Bureau which officially sets the cost of energy.

In fact, bondholders, who haven’t been paid a penny for eight years, sought to raise rates on each and every PR resident by charging a $26 “connectivity charge” every month for 50 years as a way to recover their investment losses. This proposal was shot down by the FOMB.

At the same time, LUMA has made missteps in contracting and PR. First, the company wants local contractors to hire unionized workers from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, which pays three times the rate of workers in Puerto Rico. In another blunder, the company gave a contract for 60$ million dollars to Centurion Group, a contractor, which came into existence only a few months before, and happened to hire Todd McLaren, a LUMA executive. These moves, as well as English-only press conferences, have not gone over well.

LUMA Energy, the private blackout monopoly that the USA imposed in Puerto Rico, routinely gives English-only press conferences to a population that mostly doesn't speak it. A spokesman just today retorted to a complaining journalist that "Puerto Rico has two official languages." https://t.co/wOe9Qxtpd6

— midnucas #FueraLUMA 🇵🇷 (@midnucas) August 18, 2022

The Bondholders

On the other side are the hedge funds and other bondholders that bought the distressed debt of PREPA. Hedge funds tend to keep a low profile and operate behind the scenes, quietly pulling the strings of politicians and sicking their attorneys on whoever hurts their profits.

For years, PREPA, a company that had financial records little better than FTX, was able to raise billions on Wall Street and investors took the plunge, against all sense. The deal was enticing, but the parties must have known that the public utility was insolvent. However, PREPA’s bonds were underwritten by reputable banks like Morgan Stanley and Barclay’s and they were triple tax-exempt, and investors could evade state, local, and federal taxes.

Several of the investors that invested in PREPA bonds are seasoned vultures who already plied their trade in Greece and Argentina, as well as Detroit. There’s Angelo Gordon & Company, which notified investors in 2019 that its Puerto Rican bet had paid off, offering the strongest performance of any strategy the AG Super Fund employed.

In addition, hedge funds like Oppenheimer Funds, Franklin Templeton Investments, Aurelius Management, Elliott Asset Management, Blue Mountain Capital, D.E. Shaw Galvanic Portfolios, Knighthead Capital, Marathon Asset Management, and Franklin mutual fund also sunk money into PREPA’s bonds, and they counted on Puerto Rico in general and PREPA, in particular, being unable to claim bankruptcy.

When these kinds of companies get involved, half a dozen powerful men can bring a country like Puerto Rico to its knees. They command armies of attorneys and they have the personal numbers of people of Congress.

It looked like investors couldn’t lose. The issuers would be forced to refinance, and the money managers would laugh all the way to the bank. However, the bankruptcy of Puerto Rico is like no other in U.S. history because the banks and creditors have PREPA over the barrel indefinitely.

For many bondholders, this was making the best of a bad situation. After the hedge funds exit their trades, many bond investors tend to be retirees looking for stable investments, and these less sophisticated investors had no idea what they were getting into. Puerto Rico is governed unlike any other U.S. state or territory.

In Puerto Rico, there are no laws against pay-to-play and there is no method to expose shell companies created by “politically exposed persons.” And the FOMB doesn’t pay much attention to how the taxpayer funds are spent.

Although the FOMB was given subpoena power in Puerto Rico, it hasn’t used it to change the status quo, described by bond researcher and journalist Cate Long as follows:

"Competition is the exception, not the rule" in Puerto Rico government contracting. This is one of primary causes of the bankruptcy in my opinion. OBoard has made zero efforts in this area & substantial questions have arisen on @mckinsey's role in OB contract review. #muniland pic.twitter.com/sfeowvB4u8

— Cate Long (@cate_long) November 17, 2022

Politically Connected Contractors

As PREPA underwent privatization, a gaggle of politically connected American contractors got big contracts. McKinsey came in early on to advise both FOMB and various contractors while the firm was invested in a hedge fund selling PREPA bonds.

Congress exposed McKinsey’s conflicts and the SEC later fined the firm for inadequately disclosing their conflicts of interest, but the damage was done to the restructuring process – because a host of McKinsey’s (undisclosed) clients later landed contracts in Puerto Rico.

Most importantly, one of LUMA’s parent companies, Quanta Services, was McKinsey’s client, at the same time McKinsey managed the restructuring and privatization process working for the FOMB. When this was revealed, the FOMB refused to fire McKinsey, despite public (and Congressional) outcry.

Then, there was a tiny firm in financial trouble called Whitefish Energy that seem to get the contract solely because the founder was neighbors with Ryan Zinke, Trump’s Interior Secretary, who had donated to Trump’s campaign, which was often enough to get cronies an ambassadorship. Whitefish was issued a non-compete contract worth up to $300 million.

Whitefish, a holding company, had only existed for two years and had only two full-time employees, relying on subcontractors to actually do the work. For its short stint in Puerto Rico, Whitefish Energy charged exorbitant rates for its workers.

After a national uproar, the contract with Whitefish was canceled and an FBI investigation into the controversy was initiated. After leaving his Secretary post in a cloud of corruption, Zinke won a seat in the House of Representatives for one of two districts in Montana in November 2022. Talk about failing upwards.

All this has cast a pall over the privatization process, and although it can be difficult to sort out who is really at fault and whose claims should be honored, it’s clear that Puerto Rico should be able to govern itself, especially if it doesn’t have any representation in U.S. Congress. But that’s not the way Uncle Sam does things, apparently.

(2) The @FOMBPR is a $billion enterprise and a feeding frenzy for consultants and lawyers who profit from the delay in completion of the @AEEONLINE restructuring. It’s time to end this bacchanal of taxpayer spending and to return power to Puerto Rico’s elected leaders.

— Justin Peterson (@JPHusker_) October 14, 2022

Venal Politicians

Compounding the crisis, very few people in Congress actually care about Puerto Rico. You can count them on the fingers of one hand: Either they are from Puerto Rico like Representative Nydia Velazquez (D-NY) or have Puerto Ricans in their districts like Representative Alicia Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Senator Rick Scott (R-FL), head of the National Republican Senatorial Committee. Some like Chris Christie, former governor of New Jersey, who PREPA hired as a consultant for the low-low price of $28,000 per month, may have just enjoyed Puerto Rico as a vacation destination.

As an example of how patronage works in U.S. politics, the case of Rick Scott is a perfect illustration. Scott and his wife invested at least $5 million from four trusts and a family partnership into the AG Superfund, which plowed $321 million in PREPA bonds, as a part of their distressed debt investing practice.

Of course, technically, Scott’s finances are tied up in a blind trust while he is in office. He said in a statement that he does not discuss his wife’s investments with her or her financial advisers. But hey, what a coincidence that Scott, while governor of Florida, lent a helping hand to Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria in 2017, while simultaneously having a financial incentive to do so.

While campaigning for the Senate in 2018, Scott helpfully stopped by Puerto Rico to advise the government on how to get back into operation.

At the time, Scott’s Senate opponent Bill Nelson’s campaign spokesman commented, “Rick Scott reportedly used Hurricane Michael devastation as the backdrop to film his new political TV ad. Now, we learn he had a financial link to rebuilding Puerto Rico’s power grid after Hurricane Maria. It seems the only person Rick Scott is ever looking out for is himself.”

Scott’s campaign spokesman Chris Hartline told the Orlando Sentinel, “the idea that he did what he did for Puerto Rico had anything to do with anything other than the people of Puerto Rico is just an insulting suggestion, not just for him but for the people of Puerto Rico.”

Puerto Rican politicians were later invited to pay tribute to his campaign and Scott came out in favor of Puerto Rican statehood, although he stopped short of co-sponsoring the bill to put it to a vote.

The LUMA Contract Renewed by PR Congress

The PR government has been under pressure to sever the contract with LUMA, but the road after that drastic move is unclear, but it’s open if LUMA does not meet its own KPIs for three years. The PR governor Pierluisi recently said he will not allow the contract to be canceled due to the difficulty of replacing the contractor.

The FOMB recommended renewing the contract, stating that PREPA’s previous monopoly led to a “dead end” and that “an objective review of LUMA’s performance over its first 18 months supports the conclusion that the [contract]… is the best opportunity to achieve a reliable, modern and affordable energy system.”

So, on November 30, against heated opposition, Governor Perluisi renewed LUMA’s contract for the full monty – 15 years.

After LUMA submitted its fiscal plan for the electrical system, the FOMB found various issues with the plan. The list itself is indicative of the scale of the challenge LUMA confronts as the de facto responsible party for solving Puerto Rico’s complex environmental and financial crisis.

The FOMB wants LUMA to reorganize PREPA and figure out what to do with its debts. They also must provide a plan for savings fuel procurement, which PREPA had been corruptly obtaining from Venezuela.

LUMA must also create a coordinated plan for capital projects without running a budget deficit, fund the pension system, and solve the historical problem with maintenance spending, all the while pleasing environmental conservationists with its management of vegetation.

LUMA’s leaders have their work cut out for them. And the Puerto Rican press will be there, kicking them in the caboose every step of the way. However, nobody seems satisfied with the current state of affairs, not the bondholders who have taken a costly haircut, not the staff at LUMA who feel unfairly maligned, not the utility workers from PREPA, most of whom didn’t get hired at LUMA, not the politicians who lack leverage against LUMA now, and certainly not Puerto Ricans who pay twice as much for unstable power. But hell, if all the parties are pissed off, maybe that’s a mark of a good compromise.

The case of the Puerto Rican bond fraud and debt restructuring, as well as the natural disaster-induced energy crisis and the public utility privatization, will likely go down in history as one of the most complex and controversial financial and environmental crises of the 21st century. Sadly, the real history will probably only be remembered in Puerto Rico.

Author: Tim Tolka, writer, journalist, and BI researcher

The editorial team at #DisruptionBanking has taken all precautions to ensure that no persons or organizations have been adversely affected or offered any sort of financial advice in this article. This article is most definitely not financial advice.

Revisit Part 1 of our 3-Part story:

Who are the people behind the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority and why are they not being held accountable?

— #DisruptionBanking (@DisruptionBank) November 3, 2022

Find out more in Part One of a Two Part Story about the Great #PeurtoRico #BondFraud with Tim Tolka: https://t.co/5rtWdejgJh