Africa’s agriculture sector has promising potential. The continent has 65% of the world’s remaining uncultivated arable land, an abundance of freshwater, and about 300 days of sunshine each year, according to the African Development Bank (AfDB). The Africa-focused multilateral lender estimates that around 60% of the continent’s working population is engaged in agriculture, highlighting the availability of local labour to drive the sector’s future growth.

It’s no surprise, then, that many political and business leaders, investors, and policymakers – including the likes of Africa’s richest man Aliko Dangote, and Qu Dongyu, Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) – believe that Africa has the potential to be the world’s food basket.

A Grim Reality

The cruel irony is that, despite Africa’s agricultural potential, the volume of food production on the continent is hardly sufficient to meet local demand. Most African countries heavily rely on food imports to feed their people, with the African Union estimating that the continent currently imports around 40% of its food. Experts have warned that, if Africa’s local food production does not catch up, the continent’s food import bill could double from the current $50 billion a year to $110 billion annually by 2030.

Chronic under-investment in African agriculture is one of the main reasons why the continent’s agricultural output has failed to catch up with demand. “Rural economies, and especially agriculture, have suffered an underinvestment problem for many decades,” notes Alvaro Lario, President of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), in a recent interview with Kenyan newspaper The East African, where he discussed the state of food systems and production in Africa.

Some of the challenges that have curbed investors’ appetite for investment in African agriculture include low farm productivity, high costs of inputs, unavailability and unaffordability of credit, limited access to financial services like insurance, challenges with expanding land under cultivation, limited irrigation and low levels of mechanisation, inadequate public investments in infrastructure, and farmers’ limited capacity to respond to the emerging threat of climate change.

Staple food prices in sub-Saharan Africa surged by an average 23.9% in 2020-22—the most since the 2008 global financial crisis. Our #IMFBlog looks at the drivers of food prices. https://t.co/RCaIlpFQmi pic.twitter.com/lJSktZdzfz

— IMF (@IMFNews) December 25, 2022

Limitations of African Farming

The well documented benefits that come with economies of scale, such as cost competitiveness and improved production, are not enjoyed by most farmers in Africa due to the pervasiveness of the smallholder farming model. FAO describes a smallholder as a farmer working on less than 10 hectares. The vast majority of farmers in Africa fit this description. The largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa Nigeria, for example, has fewer than 100 farms larger than 50 hectares, as per a McKinsey study.

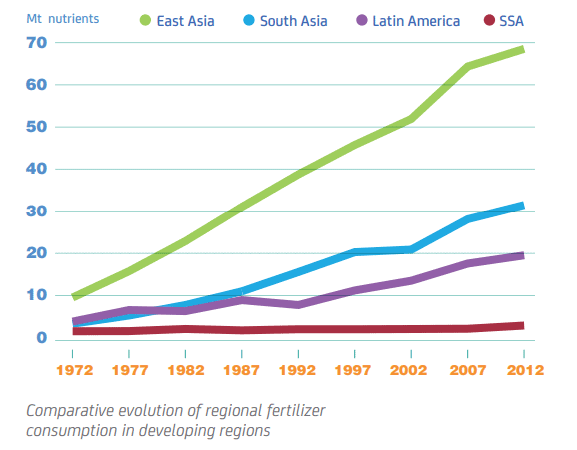

The small size of farms in Africa, coupled with socioeconomic challenges in rural economies such as low incomes, poor infrastructure and lower education levels, makes modernizing farming on the continent an uphill task. The use of fertilizer, for example, is notably low across African farms due to challenges with affordability and training on proper application. Data from Statista shows that fertilizer use in Africa as of 2021 averaged around 25.6 kilograms per hectare of cropland area – a very low figure compared to the world average of about 118.6 kilograms that year.

Source: Fertilizer Facts

McKinsey notes that most farmers in Africa lack the risk mitigations found in other regions. These include crop insurance, government welfare plans, and guaranteed offtake. Moreover, lack of government-backed initiatives to cushion farmers from persistently high food inflation has compelled many of them to focus on growing crops for their own subsistence as opposed to higher-value non food crops.

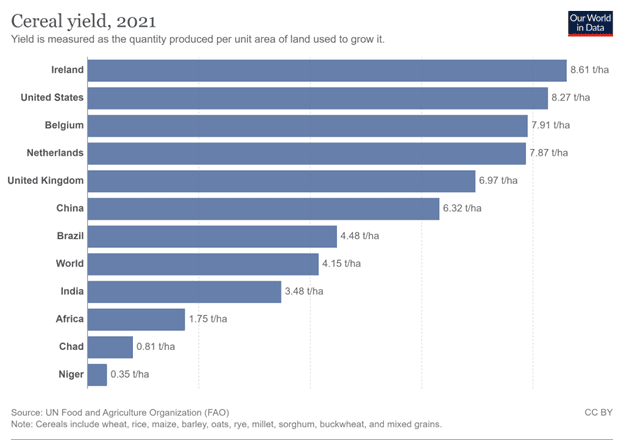

These factors collectively contribute to low farm productivity, explaining the low investor interest in African agriculture. Crop yields in Africa are significantly low when compared with other regions. For example, Africa’s average cereal yield (cereals include crops such as maize, rice, wheat, barley, rye, millet, and other grains) was 1.75 tonnes per hectare in 2021, according to FAO. In contrast, the global average was 4.15 tonnes per hectare.

Source: Our World in Data

Consolidating smallholder farmers through cooperatives, improving access to credit and insurance, improving the acreage of land under irrigation, and investing in agricultural extension services to ensure farmers get proper technical support have all been proposed by experts as possible solutions to the problems ailing Africa’s agriculture sector. These interventions will, however, only be successful if governments across Africa step up public funding to agriculture.

African governments in 2003 and 2014 made commitments through the AU to spend up to 10% of their national budgets on food agriculture. Few African countries have achieved this today due to fiscal challenges. Despite this, the need to step up public investment in agriculture has increased in light of recent challenges such as climate change. Political will is therefore indispensable to Africa’s dream of being the world’s food basket.

Pockets of Opportunity

It is, however, not all gloom and doom in African agriculture. There are pockets of opportunity and growth that some investors have taken advantage of. This is particularly true when it comes to the farming of select cash crops such as coffee, tea, and processed horticulture in East Africa as well as cocoa in West Africa. The firms operating in these value chains are well established and serve global export markets.

Most of them receive their revenue in dollars and pay their bills in local currency. This is highly advantageous at a time when many African currencies have lost significant value against the dollar. Unsurprisingly, these firms have performed well financially in recent years in view of the persistent food inflation that has pushed the prices of commodities higher relative to historical averages.

Some of these publicly listed agricultural firms, like Kenya’s Kakuzi, are cross-listed on major exchanges such as the London Stock Exchange. However, most are not listed on major exchanges but trade on the local stock markets of the countries they are domiciled in. They have generally performed reasonably well in recent years due to higher commodity prices and the impact of the stronger dollar on their earnings. This has resulted in decent capital gains and hefty dividends for holders of their stocks.

African Financials maintains an updated list of publicly traded agricultural firms in Africa that can potentially give investors exposure to these opportunities. While the potential for returns are high when investing in these stocks, the risks that come with investing in frontier markets need to be closely considered. These include issues such as liquidity for some stocks as well as foreign exchange risks. Investors also need to be mindful of other risks generally, including the often overlooked fact that past results are not indicative of future performance.

The other route for investors looking for returns in African agriculture is through private investment in digital solutions targeting different sections of the agriculture value chain. These digital solutions have attracted an influx of funding in recent years due to their potential to address entrenched challenges such as market access, training and availability of credit. According to the Africa AgriFoodTech Investment Report 2022, tech investments in African agriculture hit $482.3 million in 2021, up from $185 million in 2020. The challenge for now is that most investments are limited to Nigeria, Kenya, Egypt, and South Africa, which accounted for 92.2% of all capital raised in 2021. The lack of vibrant venture capital markets outside these hubs is a challenge for investors looking at doing business in other countries in Africa.

Africa urgently needs climate-resilient agriculture and sustainable food systems. The continent's climate agenda must include African leaders taking seriously the Maputo Protocol commitments to invest at least 10% of their national budget in agriculture. #ACS2023 pic.twitter.com/Jt3ryfkpwo

— Oxfam South Africa (@OxfamSA) September 4, 2023

Food demand in Africa will continue growing robustly in the coming decades due to the continent’s rapid population growth rate. According to UN projections, sub-Saharan Africa’s population will nearly double to more than 2 billion by 2050. The region is growing three times faster than the global average. This huge population growth represents an opportunity for investment in agriculture. Sustained reforms are, however, needed to win investor confidence and mobilise global capital on competitive and attractive terms.

Author: Acutel

We are global investors who invest in good companies at fair valuation and speculate on all else subject to the risk exposure we can afford.

The editorial team at #DisruptionBanking has taken all precautions to ensure that no persons or organisations have been adversely affected or offered any sort of financial advice in this article. This article is most definitely not financial advice.