There is currently a considerable amount of market optimism surrounding the performance of Japanese stocks. The Nikkei 225 – the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s price-weighted index that is calculated daily by the Nihon Keizai Shimbun newspaper – has been driven up to over 29,000 Japanese Yen (JPY), its highest level since 1991. Some might say there Is a Puzzle to unravel In this:

Japan's Nikkei index climbed a 30-year-high to 29,000, as investors welcomed positive earnings reports and progress around U.S. stimulus talks. https://t.co/ZvsrI7EZMI

— Nikkei Asia (@NikkeiAsia) February 8, 2021

As Stefan Wagstyl pointed out in a Financial Times article last month, this recent surge may be the result of Shinzo Abe and Yoshihide Suga’s corporate reforms designed to improve the transparency of Japan’s traditionally opaque boardroom structure. Despite associations with economic stagnancy, Wagstyl argues that Japan has many underappreciated characteristics as an investment hub.

It is ‘a land of huge scale and sophistication, with 126 million people and the world’s third largest economy. Well-educated workers, life-long corporate training regimes, effective public transport and well-established institutions make Japan a safe and efficient place to work – and invest.’

Finding Tokyo’s hidden treasures https://t.co/1AOi4umled | opinion

— Financial Times (@FT) January 22, 2021

Japan is home to technological leaders, is in close geographical proximity to east Asian growth markets and is emerging from the coronavirus pandemic in better shape than many.

Whilst these reasons for optimism are not wholly unfounded, there is also a huge systemic risk in the Japanese market which many investors are not appreciating – the fate of the Japanese Yen (JPY).

The Bank of Japan removes limits on purchases of government bonds, joining global counterparts in their unprecedented expansion of monetary stimulus https://t.co/DSlkC3oIeE pic.twitter.com/O8jkSNfiYs

— Bloomberg Markets (@markets) April 27, 2020

In response to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, last April the Bank of Japan (BOJ) pledged to purchase an ‘unlimited’ quantity of Japanese government bonds. This represented a further expansion of its already sizeable quantitative easing (QE) programme, up from a previous limit of 80 trillion JPY per year.

It is usually a pretty straightforward market rule that extensive, let alone ‘unlimited’, QE will weaken a currency significantly. A dramatic destabilisation of the yen would inevitably make Japanese stocks less attractive.

Securing the Yen

Over the last few years, trading the yen has been stable on the foreign exchange markets. In 2019, USD/JPY traded in a range of just 7.6% – its tightest since 1980. In the three years previous, its trading range was less than 10% in each year. This is in stark contrast to the larger moves we have seen historically, particularly in the period before JPY acquired its safe-haven status in the early 2000s.

Stability is important for any currency. Investors need to be confident that the yen is secure, and that participating in the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) does not expose them too harshly to detrimental foreign exchange movements.

The Japanese Yen is at risk of extending recent losses against its major counterparts, as positive fundamentals weigh on the haven-associated currency. Key levels to watch for AUD/JPY, NZD/JPY and USD/JPY. Get your market update from @DanielGMoss here:https://t.co/ntXf0jBhDa pic.twitter.com/PzmQm27avo

— DailyFX (@DailyFX) February 10, 2021

But by pumping trillions of additional yen into the foreign exchange market, how can the value of JPY go anywhere but (steeply) down?

There are various short-term reasons which explain why the Japanese yen (JPY) remains stable on the foreign exchange markets – at least for now.

The first is that JPY commands a safe-haven status, with investors flocking to it in times of crisis. The reasons for this are debated. Some argue that because Japanese investors have a net positive foreign asset position, in uncertain times they sell their foreign assets defensively and repatriate their capital, leading to a flow into JPY. Because JPY also offers very low interest rates (minus 0.10% currently) it is a common currency for cheap borrowing.

Many investors use JPY for carry trades – borrowing in a cheap currency and using it to buy higher-yielding assets.

An economic or political crisis, however, results in investors selling their assets and borrowing less. To cover their short positions they often need to purchase JPY, again causing a boost to JPY.

The yen is also a safe-haven simply because that is what market participants consider it to be. Investors shift towards JPY during turbulent times as that is what market habits and traditions have taught them to do.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic last year, and with lockdowns ongoing across much of Europe and around the world, it is unsurprising that there is a continued defensive demand for JPY. Like the US Dollar, JPY has a global market status – and wider market role – that makes its value subject to international and not just domestic factors. Hence there is a continued demand for JPY despite the loose monetary policies pursued by its national bank.

This defensive bid on JPY for now may shield the yen from the BOJ’s loose policies but, as risk appetite gradually increases, this may not always prove to be the case. Indeed, according to some, the yen’s safe-haven status itself may not always be assured. Either of these potential developments could expose JPY to more dramatic price movement.

Why the Japanese yen is not the haven asset it once was https://t.co/H9yDFt7ywo

— Financial Times (@FT) January 14, 2020

Bond markets In Japan

Because of the pandemic, investors have also flooded into Japanese government bonds which, like US Treasury bonds, are also considered a safe-haven asset. Such is the extent of this demand that yields on two and five year government bonds are below zero: at time of writing, the JGB two year yield stood at minus 0.14% and five year yield at minus 0.11%.

In effect this means that the Japanese authorities are, in the short-term, being paid to borrow money. Again this may partly explain the lack of a market reaction to the BOJ’s huge QE programme: if they are being paid to borrow money, why not borrow unlimited amounts? It makes a kind of perverse sense but may cause serious problems further down the line.

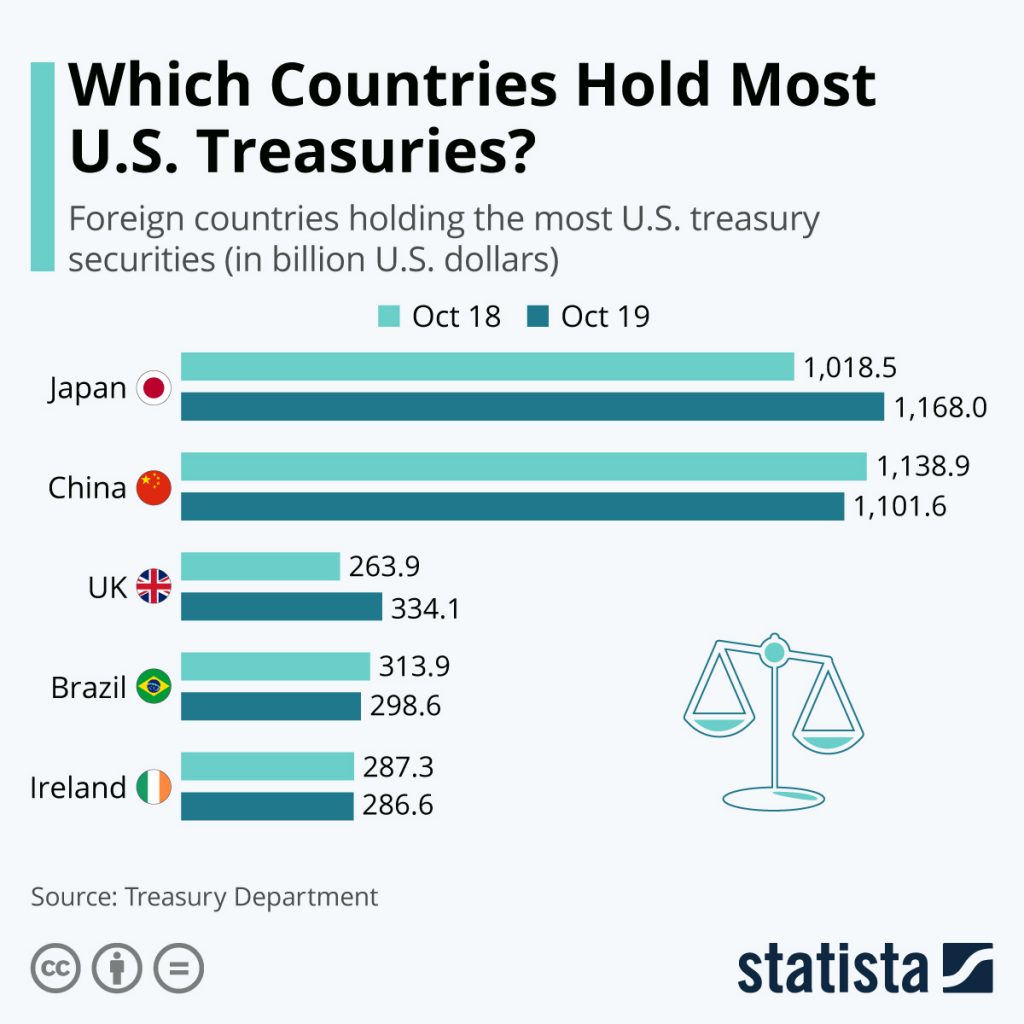

Recently we have also seen a rise in the value of longer-dated Japanese bond yields compared to those of other developed nations. Consequently, Japanese investors have seen a shrinking premium from buying overseas assets such as US Treasuries and French government bonds.

Those whose yields remained higher – such as Spanish and Italian bonds – were considered to pose unacceptable amounts of risk. When you also take into account the cost of foreign currency hedging, in many cases it has become preferable for domestic Japanese investors to purchase their own government’s bonds rather than venture abroad.

Japan’s investment in high-risk bonds is one of the reasons the yen is still a safe haven. Insights via @CMEGroup pic.twitter.com/812HQXZjPm

— Bloomberg Quicktake (@Quicktake) October 6, 2020

Of course, this trend may change and foreign yields may improve. Whilst in the short-term bearish Japanese investors have helped strengthen JPY – by repatriating yen in order to purchase Japanese government bonds – this may not always be the case. A future shift back towards foreign bond purchasing could deny the yen a source of its recent demand. This could happen sooner rather than later.

Quantitative Easing as a response

Despite these recent boosts to the yen, the systemic risk remains that quantitative easing (QE) in Japan will be of both a scale and timeframe that ultimately is unviable. Whilst it is true that QE has become a more conventional response to economic crises, most other major economies have indicated both a limit to, and deadline for, their QE programmes.

For example, the European Central Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) has a deadline of March 2022 (with any proceeds reinvested until the end of 2023) and a clear limit of 1850 billion EUR. The ECB has also been keen to emphasise that this is very much a maximum and the full amount does not necessarily need to be used.

The Bank of England and Federal Reserve have also indicated both time-frames and limits for their (albeit sizeable) QE programmes. These programmes have of course proven to be flexible in size and duration as the pandemic continues to develop. Nonetheless, the markets nonetheless remain confident that these QE programmes remain a limited measure and a response to extraordinary times – crucially, not an endless and permanent policy for encouraging growth.

The markets cannot make the same assumption about Japan. The BOJ has repeatedly emphasised that their QE programme is ‘unlimited’ in scope and length. This may explain the rising longer-dated bond yields in the country, indicating greater long-term risk conditions. Could these yields suggest the existence of economic problems the market, distracted by the current crisis, is not adequately considering?

The yen may cause serious problems for the TSE and wider Japanese economy in the long-term. Whilst there are various short-term market factors that are currently keeping it buoyant, we cannot assume that this will continue indefinitely, particularly when the JPY’s safe-haven bid is no longer as apparent.

Unlimited QE – which has itself failed to generate the stable inflation it was designed to do – may ultimately destabilise the yen and thereby endanger foreign participation in the TSE.

For now, the TSE benefits from the tens of trillions of free yen the Bank of Japan continues to pump into the stock exchange and Japanese economy. Investors foreign and domestic may for now enjoy riding the wave this has created. But both should be aware that the Japanese yen is trading on shaky foundations.

Author: Harry Clynch

#TSE #JPY #Yen #SafeHaven #Nikkei #QuantitativeEasing #Stability #Secure #BankofJapan

One Response