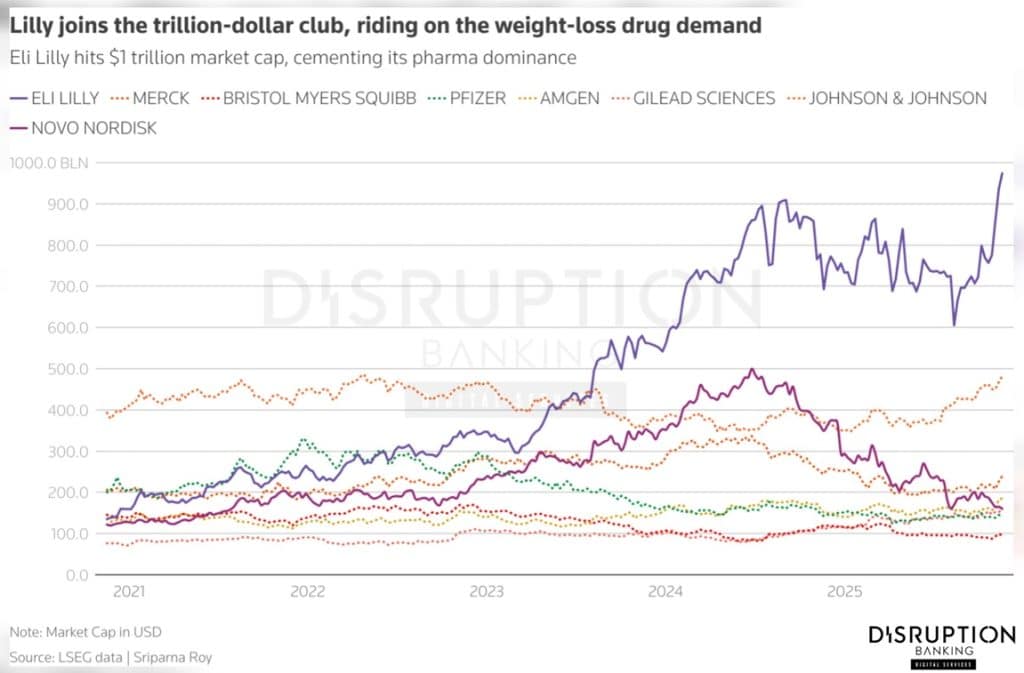

Eli Lilly & Co. (ticker: LLY) has quietly become a titan of Wall Street. Fuelled by two blockbuster Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP‑1) drugs (Mounjaro for diabetes and Zepbound for obesity), Lilly’s stock leapt from under $100 in 2018 to $1,010 at the time of writing (TradingView), making Eli Lilly the world’s 10th most valuable company overall. The aforementioned drugs drove revenue up 45% year-over-year through the first nine months of 2025. As a result, Eli Lilly’s market cap briefly topped $1 trillion on November 21, the first drugmaker ever to join the “trillion-dollar club.”

By comparison, traditional Dow‐30 healthcare names like Johnson & Johnson and Merck are only a fraction of that size. Lilly’s value now more than doubles J&J’s. The company briefly touched $1,200 per share in October. Its market cap today sits north of $950 billion.

Yet when you scan the list of 30 Dow components, Lilly remains conspicuously absent.

The Dow’s Old‑School Formula

The Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) isn’t a broad market index. It’s a hand‑picked list of 30 big U.S. companies chosen by a committee. Unlike the S&P 500, which weights companies by market capitalization, the Dow is price weighted. That means a stock’s per-share price dictates its index influence, not its total size. In practice, a $1,000 stock carries ten times the weight of a $100 stock, even if the latter company is much larger in market cap.

One analysis quipped that after Nvidia’s 10-for-1 stock split (taking its price from $1,200 to $120), it “became a potential contender” for the Dow. Without splits, sky-high share prices would let a single stock dominate the Dow entirely, Nvidia was left with little choice but to split its shares to join the Dow. Because of this quirk, the Dow’s small component list is picked conservatively.

S&P Dow Jones Indices say there are no hard numerical rules. New members must simply have an “excellent reputation,” sustained growth, and broad investor appeal. In effect, the Dow committee aims for household-name businesses that feel like the economy’s backbone.

Critics note that with only 30 stocks, this approach leaves out whole swaths of the market and makes the index a poor proxy for modern U.S. equity markets.

Lilly’s Meteoric Rise vs. the Dow’s Lens

Eli Lilly now dwarfs most Dow components. Its GLP‑1 drove drug sales to record highs, even surpassing Merck’s Keytruda as the world’s top-selling medicine. Lilly’s recent quarter saw $10 billion from its diabetes/obesity portfolio, more than half of total revenue.

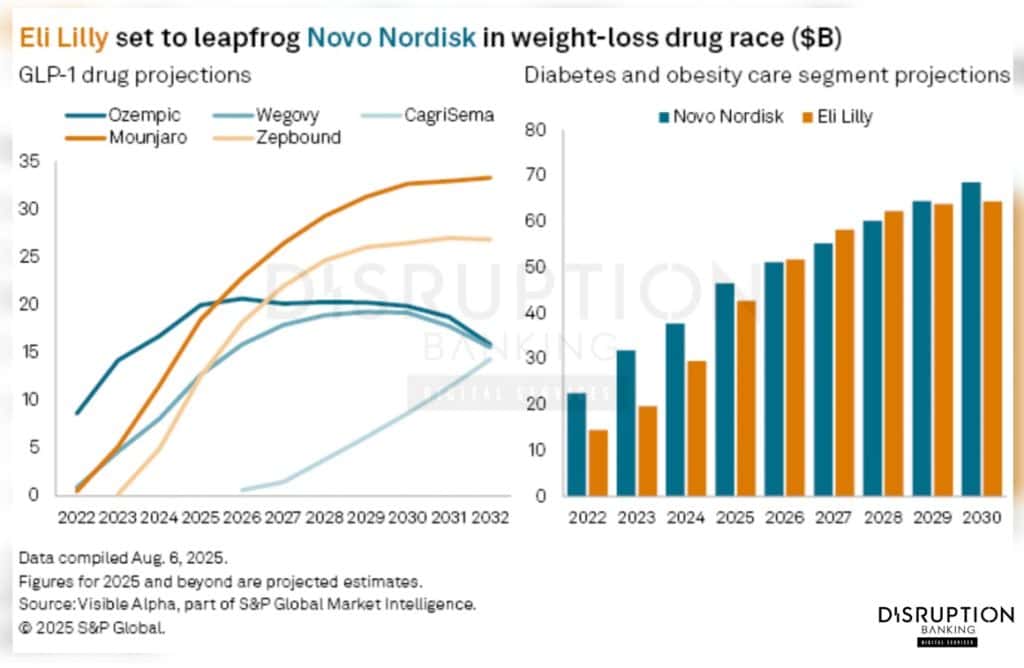

The company has captured 57% of the U.S. obesity market and 60% of injectable obesity and diabetes prescriptions. The GLP-1 market is projected to exceed $100 billion by 2030. Analysts expect Lilly’s tirzepatide sales to surpass rival Novo Nordisk‘s by 2026, with Mounjaro projected to hit $18.4 billion in 2025 and $22.8 billion in 2026. Zepbound is expected to jump to $12.5 billion in 2025 and $18.1 billion in 2026.

LLY stock now trades around $1,010. For context, Goldman Sachs GS, the highest-priced Dow member, is under $840. By market cap, Lilly ($~1 trillion) is roughly two-thirds the value of Meta Platforms and greater than Walmart WMT, and more than double of J&J’s valuation. It even earns comparisons to tech’s elite.

Director of Biopharma Equity Research at Deutsche Bank, James Shin, says Lilly is again “resembling the ‘Magnificent Seven,’” comparing it to the ranks of Nvidia, Microsoft, and others at the cutting edge of Tech.

Lilly has literally reshaped the pharmaceutical industry in months. Yet the Dow’s rigid formula sees only a $1,000‑a‑share stock and a fifth healthcare company vying for inclusion. Under a price-weighted regime, Lilly would crush the index’s balance unless it split its stock first. Historically, new entrants with high prices, such as Amazon, Apple, and Nvidia, issued splits to bring their shares in line. Lilly, by contrast, hasn’t split since 1997, so its share price remains an outlier.

Why isn’t Lilly in the Dow Jones?

Mechanics. A $1,000‑share Lilly would overwhelm the Dow’s calculation. The index’s divisor is adjusted for splits so the index doesn’t jump on corporate actions, but without a Lilly split, one company would carry a huge weight. In a price-weighted index, “the higher or more expensive the share price, the larger a company’s weighting.” The Dow committee has routinely demanded splits to avoid this problem, and Lilly has chosen not to. Until it brings its price down (for example, a 10-for-1 split to $100 per share), the math alone argues against adding Lilly.

Sector Balance. The Dow is also sensitive to sector representation. It currently includes four healthcare/biotech firms: Johnson & Johnson, Merck, UnitedHealth and Amgen. Together they already give healthcare a hefty slice of the index. Adding Lilly, a pure-play pharmaceutical giant, would push that slice even higher while other sectors (consumer goods, tech, industrials) lose ground. The Dow’s committee has historically tried to avoid overloading any one industry. Even BlackRock’s exclusion from the Dow was partly due to the finance sector already being richly represented. Lilly’s case is similar: the index “feels” it has health care covered, so another drugmaker isn’t necessary.

Narrative Fit. Finally, there’s a judgment call about what the Dow is “supposed” to represent. By convention, the Dow features companies with visible, tangible products or services, from soda to airplanes to semiconductors. A pharmaceutical research company, no matter how profitable, might not fit the committee’s ideal of a “blue-chip industrial.” Lilly does sell insulin pens and devices for consumers, but its growth story is driven by specialized drugs and pipeline bets, not mass-market consumer brands. The committee prefers firms that feel like broad economic pillars.

As Investopedia notes, Dow members must be part of America’s “backbone” industries. In the committee’s eyes, maybe the Index already gets sufficient health/medicine exposure from J&J and Merck.

Notably, there is no official information available explaining Lilly’s exclusion. The S&P Dow Jones team simply “does not comment or speculate on index changes.” We can only infer. But by the Dow’s own terms: price-weighting, sector balance, and narrative continuity, leaving Lilly out is consistent with how the index has operated for decades.

What the Omission Really Tells Us

The outcome isn’t Lilly’s fault; it’s a symptom of the Dow’s archaic design. A trillion-dollar company missing from the DJIA highlights how much the index lags the real market. The Dow is still telling a twentieth-century story of American business, focusing on “things,” cars, food, banks, energy, rather than the new engines of growth. Meanwhile, Lilly profits from managing weight loss on a national scale. Its influence on health care spending and markets is enormous, yet that power is invisible if you only watch the Dow ticker.

All in all, the Dow remains a curated snapshot, not a market encyclopaedia. Its decision to leave out Eli Lilly protects the index’s own mechanical logic, but it also admits something bigger: the Dow’s lens no longer captures where money actually flows.

From the standpoint of real capital, Lilly is a modern titan of the U.S. economy.

The reality is straightforward. The most famous U.S. index doesn’t always include the biggest players shaping the market today. Lilly’s absence shows that the DJIA is still governed by past conventions and rigid mechanics rather than today’s rising power centers.

Author: Richardson Chinonyerem

The editorial team at #DisruptionBanking has taken all precautions to ensure that no persons or organizations have been adversely affected or offered any sort of financial advice in this article. This article is most definitely not financial advice.

See Also:

A Company-by-Company Look at the Dow Jones Index | Disruption Banking

How Merck’s Biotech Edge Powers Dow Jones Gains | Disruption Banking