By David Whitehouse

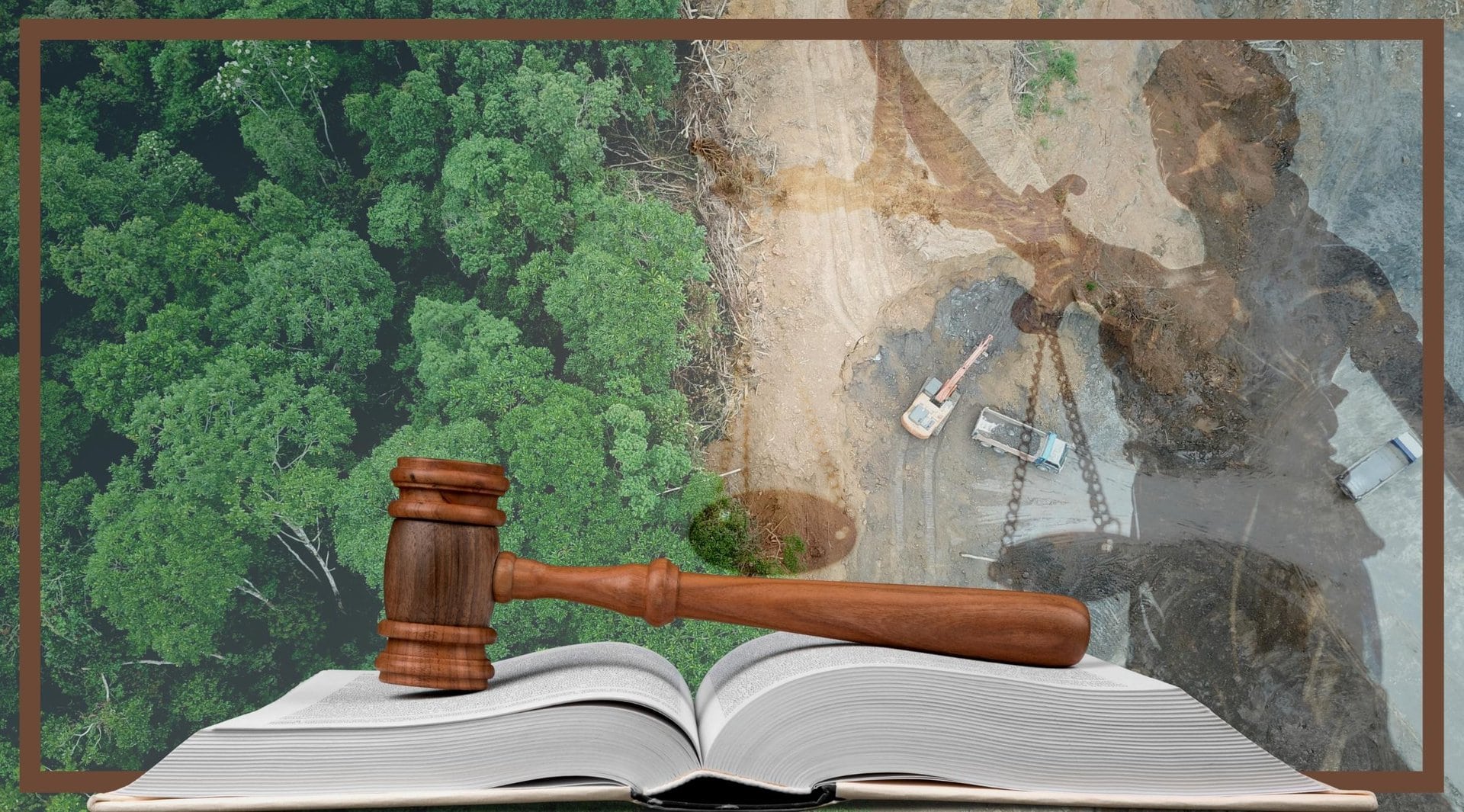

Outdated corporate laws drawn up in the nineteenth century to protect the interests of shareholders need a revamp to tackle twenty-first century climate concerns.

Corporate laws, which define the purposes of companies and the responsibilities of directors, are a core obstacle on the path of the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, says Simon Puleston-Jones, CEO of London-based Climate Solutions.

Currently companies are legally obliged to serve the interests of shareholders, but the conflict between the interests of business owners and society opened up by global warming and the need for a transition to renewable energy means that redefinition is needed, he argues.

“The economics of ‘dirty’ businesses are currently attractive at corporate but not societal level,” Puleston-Jones says. “The single most important change for the energy transition” would be to change the focus of corporate laws from shareholders to stakeholders, he argues. “Such a change can transform society.”

Climate Solutions helps companies raise climate-related finance from institutions. Puleston-Jones gave his views in a personal capacity. He is optimistic that such a change could happen in the UK this decade, regardless of which party is in government – though any such shift will be much more challenging in the US, he says.

There’s a need to think in broader terms than emissions, Puleston-Jones says. Stress also needs to be put on heavy water usage. Moving at a reasonable pace, he argues, should not be seen as a justification for gas as a transition fuel. Scientists such as Robert Howarth at Cornell University in the US have shown that although gas emits less carbon dioxide than coal, it has a more damaging overall impact on the environment as it gives off methane throughout its life cycle.

The average lifecycle emissions of gas are increasing as the proportion of shale gas, which gives off even more methane, is climbing, Howarth argues. Liquified natural gas (LNG) use is also increasing, and turning gas into a liquid for shipping greatly raises emissions, he writes. Puleston-Jones says there is “market disbelief” that natural gas is seen as a sustainable energy source. Gas is “being used as a defence by many companies for not being proactive.”

Outdated Assumptions

The assumptions on which British corporate law rests belong in a different century. The idea of the UK as a historically entrepreneurial nation of industrialists is an example of what historians call “invented tradition.” The Industrial Revolution took place before the legal reforms that made modern limited-liability companies possible. Only since 1844 has it been possible to create corporations without the explicit permission of the state, and freedom to incorporate as a limited liability company has only been available since 1855.

The era was blind to the possibility of long-term environmental damage as a by-product of industry. The first volume of Karl Mark’s Das Kapital, published in 1867, analyses industrial capitalist production in huge detail. But the impact of the release of emissions into the atmosphere passed Marx by completely – along with everyone else.

The evidence today is that at institutional level, increased disclosure requirements make it less likely that investors will hold on to fossil-fuel investments. A French law which came into effect in January 2016 required institutional investors, but not banks, to report annually on their climate-related exposure. This made it possible to compare the reactions of the French institutional investors with those of domestic banks, as well as financial institutions of all kinds in Europe.

A Bank of France study written by Jean-Stéphane Mésonnier and Benoit Nguyen found that investors subject to the French disclosure requirements curtailed their financing of fossil energy companies by about 40% versus investors in the control group. The impact was about as twice as large for investments in companies exploiting mostly coal and unconventional fossil fuels, such as fracking, as opposed to conventional oil and gas.

But selling assets to someone else does not in itself reduce emissions. Today, many banks and investors fail to produce meaningful carbon accounting. The Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) argues that they should “rebaseline” if, for example, they offload a coal investment, to ensure that any future reduction in emissions is achieved by operational improvements in their portfolio rather than by selling a carbon-heavy asset to someone else – which, in real world emissions terms changes, nothing at all.

PCAF is a global partnership of 279 financial institutions working to develop a harmonized approach to emissions measurement and disclosure. But rebaselining is not happening. The 2 Degrees Investing Initiative (2DII) analysed reports from 70 PCAF signatories and found that not a single one was fully compliant with PCAF standards. 2DII argues that “financial institutions face significant risks in marketing compliance with a standard that they currently do not fulfil and advertising transparency that does not meet minimum data quality standards.”

More Targets Needed

It’s important that there are buyers for “dirty” assets, Puleston-Jones argues, to avoid impairment of stranded assets. “There will be impairment of assets over time,” but this needs to happen gradually to avoid undue harm to balance sheets, while meeting climate goals at a “reasonable” pace. Policymakers need to balance financial versus environmental impacts. “It’s not an easy balance to strike.”

According to PCAF, since the Paris Climate Agreement in December 2015, the largest banks have invested more than $3.8 trillion into fossil fuels. Giel Linthorst executive director at PCAF in The Randstad, Netherlands, agrees that “stakeholder” is a better concept than “shareholder” which has become “too narrow” to address modern concerns. Debt as well as equity providers have an important role to play in pushing corporate policies forward, he argues. “Banks can play a key role in the transition.”

2DII points to the need for PCAF to enforce its own standards. The PCAF seems to believe that “regulators and civil society should enforce compliance and that the role of PCAF is limited to providing the standard, not enforcing compliance,” it says. The result is that mechanisms to enforce compliance and ensure consequences when this doesn’t happen “do not seem to exist in the PCAF universe.”

Linthorst argues that part of the problem lies with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHG). The GHG is a partnership between World Resources Institute (WRI) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) which supplies the world’s most widely used greenhouse gas accounting standards. The rebaselining questions is not treated clearly enough by the protocol, he argues. “There could be stronger guidance from the GGP on when rebasing is required.”

The wider problem, Linthorst says, is that many companies, especially small and medium-sized ones, still don’t measure emissions. “Companies firstly need to measure to set a baseline” for emissions, he says. “Even among financial institutions, only a few have set targets.”

Those targets will need to cover the entire supply chains of companies if they are to be meaningful. According to research from the Rocky Mountain Institute in the US, over 40% of GHG emissions come from industrial supply chains, yet there are no carbon accounting methods that cover entire material supply chains. The institute says that the average company’s supply-chain GHG emissions are 5.5 times higher than direct emissions from its own operations.

Retail, hospitality, manufacturing, food, services and biotech all have above-average ratios of supply-chain to direct emissions, the research finds. Mining and mineral processing companies are well positioned to take a leading role in accounting harmonisation because they straddle several lines of supply, the institute says.

David Whitehouse is a freelance journalist in Paris.

Author: David Whitehouse